Flying Saucers & Spaghetti Monsters –– Subjective Morality

There is [No] Morality: Scientism's Moral Points of View Coalesce into Dogmatic Hedonism

Have you read Part 1 and Part 2? If not, I encourage you to do so before you read this entry, though it is not necessary. Part 1 will offer more moral context of the debate than Part 2 will, which focused chiefly on the sciences.

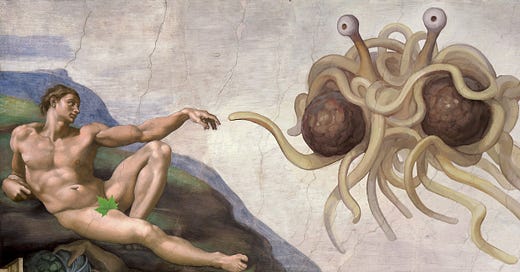

Michelangelo, The Creation of Adam ( c. 1508–1512). Fresco, Sistine Chapel's ceiling. No leaf required.

Despite all evidence to the contrary, it is not out of the ordinary for New Atheist’s to claim the moral high ground, as if God or religion is the root of all evil. It happens quite often, actually. Say you side with the late Christopher Hitchens and his “unanswerable” moral challenge, a monkey wrench of sorts: “Name me an ethical statement made or an action performed by a believer that could not have been made or performed by a non-believer. As of yet, I have had no takers.”[1] Apart from their misconception that moral actions or statements are independent of belief, intentionality, imperative, and the inner self, to be tallied like notches on a jail room wall, the burden of proof is not on the devout to come up with an answer, rather it is on Hitchens to deliver a premise for his challenge.

First, recognize that this challenge presupposes a necessary basis or way to differentiate between right and wrong, good and evil, in order for it to be answered in any concrete, meaningful sense. Second, that basis necessitates there to be, in some way, shape, or form, objective moral law lest we fall into contradiction (if everything can be good, nothing is truly good). Third, it assumes that atheism has a basis to say morality exists at all. It is to this third point that his challenge hinges upon. Rather than rinse and repeat an answer, perhaps Dawkins served it best once again:

The total amount of suffering per year in the natural world is beyond all decent contemplation. During the minute that it takes me to compose this sentence, thousands of animals are being eaten alive, many others are running for their lives, whimpering with fear, others are slowly being devoured from within by rasping parasites, thousands of all kinds are dying of starvation, thirst, and disease. It must be so. If there ever is a time of plenty, this very fact will automatically lead to an increase in the population until the natural state of starvation and misery is restored. In a universe of electrons and selfish genes, blind physical forces and genetic replication, some people are going to get hurt, other people are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice. The universe that we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is, at bottom, no design, no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.[2]

Dawkins is not alone in his amoral aspirations, the so-called “happy atheist” PZ Myers elaborates:

We do not have evidence for purpose in evolution, and if anything, all the evidence is against the idea that evolution has a direction or that natural selection can be anything but an unguided response to local conditions…. First, there is no moral law: the universe is a nasty, heartless place where most things wouldn’t mind killing you if you let them. No one is compelled to be nice…. You or anyone could go on a murder spree, and all that is stopping you is your self-interest (it is very destructive to your personal bliss to knock down your social support system) and the self-interest of others, who would try to stop you. There is nothing ‘out there’ that imposes morality on you, other than local, temporary conditions, a lot of social enculturation, and probably a bit of genetic hardwiring that you’ve inherited from ancestors who lived under similar conditions…[3]

Now, if we were truly living in a universe with “no moral law”, “no purpose, no evil, no good, nothing but pitiless indifference,” then the premise of Hitchens’ moral challenge is a table scrap on the best of days. There is no objective morality. No basis or justification to say, one way or another, that some statement or action is truly incorruptibly good that cannot become monstrously evil at some other point or place. In fact, Hitchens necessitates objective morality (or moral truth) for this challenge to carry any weight whatsoever. Hitchens can’t have his cake and eat it too. So, why pose the challenge? Was it a rouse to deconstruct religious convictions? A Freudian slip? Or was he simply mistaken?

Regardless of intention, Hitchens’ challenge suggests that morality is confined to behaviour, or at least, it is measured in such a way. This is very common. I admit, it is much easier to be cocksure of one’s moral aptitude if arrogance is conveniently left off the table of depravity; after all, it is true that not all atheists kill, rape, loot, and plunder; many even donate to charity, provide humanitarian aid in third world countries, firmly hold to the Hippocratic oath, save lives, and so on. It is not automatic, compulsory, or obligatory that an atheist must commit themselves to heinous, immoral behaviour. To assume such is nonsense. So, strictly on a behavioural level, name just one moral statement or action. On that, I am obliged.

If atheism is true, then moral relativism is true. That is to say, if our moral beliefs, attitudes, and behaviour are truly relative to dynamic contexts of a cultural framework, Hitchens’ challenge is actually about like-mannered behaviour or what society, consciously or otherwise, deems extremely important a la moralism. And on that, billions of believers around the world to date, many of whom are from Hitchens’ immediate culture, firmly hold that Church fellowship, praying, worshiping, and loving God with whole heart is an essential moral imperative, a very good thing to do. In fact, it is morally required for Christians and morally forbidden by atheists. Perhaps, that addresses the concern.

Still, this is bigger than just falsifying Hitchens’ claim. There is an open question that underpins his challenge that ought to be addressed: Supposing there is no God, can moral relativism work at all? Or is there a sustainable moral system without divine command? And what does science have to say about all this? It is to that we turn to next.

A Very Brief History of Morality in Scientism

This new moral view of the world is especially disconcerting, Sam Harris remarks, due to the copious and growing number of secular scientists, academics, and journalists who likewise believe “intellectual progress prevents us from speaking in terms of “moral truth” and, therefore, from making cross-cultural moral judgments–––or moral judgments at all…. that morality is a myth, that statements about human values are without truth conditions (and are, therefore, nonsensical)…. that there is no such thing as moral truth––only moral preference, moral opinion, and emotional reactions that we mistake for genuine knowledge of right and wrong,”[4] and that morality is nothing more than heightened nostalgia or misinterpreted sentiment that is maladaptively personalized by an objective sense of ego. This scientistic approach to ethics leads to either moral nihilism (there is no morally objective right or wrong, which is also referred amorality, the absence of morality) or moral relativism (morality is relative to its cultural framework). It should be noted, however, that these two ethical views are not mutually exclusive necessarily, given that both reject objective morals exist and fall under the purview of moral skepticism; albeit ‘skepticism’ is a strong choice of word, which seems to imply agnostic indifference, apathy, or an intermediary position of seeking as opposed to, say, presuming. Because of this dynamic and its relationship with scientism, I refer to this overarching view as scientistic moralism. This temporal, equivocal take on morality has many namesakes like subjective morality, subjectivism, epicureanism, emotivism, hedonism, and surmises in a sociopolitical variation called the social contract. In fact, it is the stereotypical view promulgated by strong scientism, that the hard sciences alone – like chemistry, biology, physics, astronomy – provide the only genuine source of facts and intellectual authority for true knowledge of reality[5]. All other views outside the scope of science – like morality, religion, theology, philosophy – are mere private, prejudice views grounded in juvenile opinions and subjective emotivism; values and opinions such as those above are not empirically verifiable (through sense experience) and, therefore, in their very nature unknowable, neither true nor false, and cannot ever be proven true. To capture the sentiment; to believe in an objective unscientific view (say, God) is to be an intolerant, bigot, fundamentalist dumb-dumb.

Over the last hundred years or so, the science-is-truth and God-is-dead hypotheses took its effect and shifted the public sense of obligation on a mass scale. Religion and morality were no longer seen as a way to obtain knowledge. It caused a fact/value distinction in academia and our cultural framework. Science is seen as pure fact: objective (independent of opinion), public, and obligatory for everyone. Religion and morality are seen as values: private, subjective (personal opinion), and culturally relative, even so far as to consider it surreal, illusory, imaginary or make-belief[6]. In short: religion a strawman, science the steelman. Theology once stood as “Queen of the sciences”, now it hardly passes as a paper bag princess.

Due to our seemingly natural inclination to universalize moral rules, scientism’s brute fact tactics, riding the coattails of industrialization and modern progress, consequentially sparked a myriad of “household facts” like religious tolerance and pluralism. Religion was a private, personal experience and, therefore, we ought to, in principle, respect one another’s privacy. This led to adverse reactions, however, that continue to run contrary to modernism’s claim to scientific authority such as postmodernism, spiritual-but-not-religious, universalization of political correctness (and now Social Justice Warriors, radical environmentalism, “wokeness”), et cetera[7]. Over the course of the twentieth century, and now well into the twenty-first, the scientistic interpretation of values is still prevalent, but it did not smother moral truth, it just pressed down hard enough to soften its voice and smoosh a new subset of perceived moral facts into plain sight. That is, “no moral truth” was replaced by “My moral truth” as the dominant axiom to live by. (Why? Well, it seems to me that we implicitly intuit the objective reality of moral truth; more on this in a bit.) The implicit long-term moral effects both secularism and scientism have shared in Western culture inevitably morphed into New Atheism’s vibrant display of sledgehammer intolerance toward religion, particularly the Abrahamic faiths (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam), of which largely contributes to, if not swells, the widespread dissemination of moral nihilism and moral relativism, where the word “moral” is used without regard for the word itself.

Scientism may posture as a brute scientific fact, but it only proves itself to be a half-congealed philosophy leaking out of naturalism. Despite the now cliché retort that this view is self-referentially incoherent – for the claim “truth can only be verified by science” is in itself untestable and unverifiable by the senses, and is, therefore, a self-refuting, unscientific opinion[8] –they still boldly claim to know for certain that morality is unknowable. Even when they can’t get their own facts straight, militant atheism marches onward hand-in-hand with scientism as its battering ram–––no, as if it is science.

What is most intriguing, however, is the outright contempt for religion or a person’s therapeutic imaginary friend (God) in light of a meaningless, “nasty, heartless,” destitute world; seems rather daft, no? If laymen who are not gifted in the sciences are not treading into scientific territory, what’s the issue? By their own standards, it’s just pointless squabbling. Yet, they feel the urge to make a stand when agnosticism is the more honest actuation of “indifference”.

This urge for “progress”, no doubt, is another way to exercise a naturalistic moral agenda, as if theism nauseates Mother Gaia’s blind, random forces so deeply, she spawned disciples to rid it of dispensation. That a brave new ‘moral’ world can be progressively carved by the scientistic method alone is a breach of its secular boundaries. It should set off the alarm.

Scientistic Moralism: Between Nihilism and Relativism

If there is no objective morality or a divine source thereof, it is no surprise, then, that scientistic moralism espouses the view that morality and justice, good and evil, virtue and vice, right and wrong, must begin and end in neurobiology. That morality is not ontologically verifiable or accessible (which is moral nihilism) only reduces morality into a matter of epistemology and biology: What we know or feel determines moral values, standards, and its consequential hierarchal structure (which is moral relativism). Given this anti-transcendent moral view dominates the stage as of late, advocates of scientism and naturalism almost unanimously agree: The truth or justification of moral judgments is not objective, absolute, or universal, it is relative to the standards, traditions, convictions, or practices of a person or group of persons.[9] –– Good to know.

Though it is a tad bit confusing; if the majority of secular scientists, academics, and atheists alike, by their own standards and convictions believe there is “no such thing as moral truth––only moral preference, moral opinion, and emotional reactions that we mistake for genuine knowledge of right and wrong” is a moral fact, an argument from silence as it were, then they are stuck in quite a pickle: if moral truth is illusory and, therefore, moral relativism is factual by default, am I, then, morally obligated or required to believe in moral relativism even if it is indeed a fact? Must I accept it, or rather, is it forbidden to not accept it? The answer, of course, is no; it’s business as usual. If I am not obligated or required to believe in moral relativism, then I am certainly not required to behave like it exists. I can believe in objective moral truth in a moral relativistic framework and still be morally consistent relativist. To each his own: ‘my [moral] truth is my truth, your [moral] truth is your truth’. Especially given the fact that there is also no objective obligation of restraint from adopting objective moral truth as a belief lest a universal moral exist: It is morally wrong to believe in moral truths. (Which, strangely enough, seems to be the push nowadays, doesn’t it?) In shorter words, there is no objective moral obligation to affirm it and no objective moral restraint to reject it. It is neither forbidden nor acceptable–––it just is (yet isn’t?). And if morality has no imperative for behaviour whatsoever, what is the point of morality at all? The ontology and epistemology do not align in a basic or operative sense, which renders our moral sense a neurobiological deficiency, in my view. A moral person is just confused.

Be that as it may, there is also a biological and moral misalignment in scientistic moralism. With no external source of objective restraint or obligation, in knowledge or reality, moral relativism and moral nihilism seem to coalesce into an incontrovertible moral hedonism, where pain, broadly speaking, is the ultimate evil and pleasure, broadly speaking, is the ultimate good. Not objectively good or evil, of course, but in a subjective sense; it still falls under the scope of moral relativism, given that scientistic moralism espouses that truth, or in this instance, moral truth can only be verified by the senses. This is all but admitted by Dawkins in a recent interview.

If someone held the “philosophical belief that inflicting pain is good” or that “suffering is wonderful”, then “you can’t actually say it’s [truly] wrong”[10]. The only rational argument and objective basis against such a detestable belief is that, in his words, “I want to live in a society where that sort of person doesn’t have influence”[11]. But there is ultimately no ground or justification to say otherwise. It is pure preference.

Dawkins goes on to say that “you could actually breed, by artificial selection, animals that like what we would think of as suffering.” And that “theoretically, I suppose, as a Darwinian I would have to say you could breed animals that like pain.” Whereby through the evolutionary process pain or suffering is meant “to teach the animal not to do again what it had just done”.

Take notice that this sense of pain or suffering is confined to personal sense experience, to feelings, it is solely self-referential and holds little to no emotional consequence if pain or suffering is inflicted on others, such as the case with murder, torture, or rape. If pain and suffering is to teach personal lessons on how to behave (what not to do), then someone else suffering is not suffering necessarily if you are the murderer, torturer, or rapist. It can still be in your best interest to do so. After all, as Dawkins already pointed out, “thousands of animals are being eaten alive” by predators that need to survive.

In light of Dawkins’ philosophically conflicting response, the interviewer Alex O’Connor poses a question: “If morality is something that’s evolved within us and was susceptible to similar arbitrariness, is the fact that ‘rape is wrong’ as arbitrary as the fact that we have five fingers instead of six?”

Dawkins ponders. “No, I don’t think so, because, once again, rape causes suffering.”

We can’t fault Dawkins for being honest; he is a morally consistent Darwinian. Consider the contradiction. Dawkins still inadvertently holds to the belief that suffering is truly wrong. But is that tenable? If morality is stimulated by a blind, arbitrary process of evolution for reproduction and survival, how then can we say that rape causes suffering is truly wrong? By all accounts, rape evolved to ensure genetic survival. If anything, it sounds evolutionarily normal, if not, normative. It may cause great pain for one, but great pleasure for the other. Then again, you can, in principle, freely breed animals (or humans) that enjoy suffering. So, again, why is the rapist truly in the wrong? By what moral standard can we say: Rape is wrong? Suffering is wrong? Pain is wrong? I don’t see how we can. In this framework, the best we can claim is that most people of a particular group may feel that suffering is wrong, where personal suffering is seen as the highest moral evil, but no universal or objective moral truth claim can be reasonably considered.

By my reckoning, it doesn’t seem to add up very well, for a number of reasons. If morality lies somewhere between preference and private opinion, and is not a public or objective concern, would that not make morality exclusive to the individual, the very opposite of inclusive, in every possible sense? How, then, could we actually share moral values? Empathy is no longer grounded in shared experience, which means communication has no bedrock for mutual edification. Altruism, self-sacrifice, or lovingkindness are not necessarily good attributes in this scenario. It is tremendously difficult, painful even, to truly love someone, to be selfless, to sacrifice something for someone else that deeply means something to you. But survival, egotism, and self-gratification may very well be the greater good. After all, you are all that’s left to consider – your survival and the quality of it, too, is pedestaled necessarily as the apex of moral consideration. That is, this empirical method for verifying morals inevitably leads to a sort of moral solipsism whereby only subjective feelings gained by sense experiences determine ‘objective’ morals to the self alone at the exclusion of other people’s sense experiences, since intersubjective sense experiences cannot truly be shared and moral conclusions drawn from experience are strictly personal, isolated opinions; it reduces moral truth to a litmus test of personal comprehension, as if only what can be experienced or known by the self is true. Scientistic moralism reinforces hyper-individualistic hedonism as a divine altar by which one must commit their life, which then, in turn, encourages experiential subjectivism (the likes of which is swollen in our immediate culture; it pedestals isolated values and the desire to fulfill desire as normative wherein self-referential pleasure is the path of least resistance and self-aggrandizement alongside mutual affirmation offers the strongest sense of absolutism, but I digress).

In other words, moral relativism does not magically do away with external or objective moral truth, it either suppresses its primacy under the guise of preference, wherein it very much lurks in the background of the decisions we make and the beliefs we hold, or it transmutes into conscious desires and ideals. It strongly suggests that we implicitly know objective moral truth exists. Harris, going against the grain of the scientistic norm, is obliged to agree, “While human beings have different moral codes, each competing view presumes its own universality. This seems to be true even of moral relativism.” He goes on to say:

Moral relativism, however, tends to be self-contradictory. Relativists say that moral truths exist only relative to a specific cultural framework–––but this claim about the status of moral truth purports to be true across all possible frameworks. In practice, relativism almost always amounts to the claim that we should be tolerant of moral difference because no moral truth can supersede any other. And yet this commitment to tolerance is not put forward as simply one relative preference among others deemed equally valid. Rather, tolerance is held to be more in line with the (universal) truth about morality than intolerance is. The contradiction here is unsurprising. Given how deeply disposed we are to make universal moral claims, I think one can reasonably doubt whether any consistent moral relativist has ever existed.[12]

Harris is dead on. This societal expectation of tolerance is espoused as a universal secular moral standard, yet it fundamentally betrays their own relativistic position. That is to say, a moral relativist may observe behavioural patterns and consider societal standards as a kind of moral, in an epistemic sense, but they are nevertheless ontological moral nihilists who subliminally and unwittingly affirm objective moral truth.

That said, it also raises a very simple question: If morality is temporal or mutable, not objective nor universal, what use is the word “moral” to qualify the word “relativism”? Rather, what does the word moral even mean in this context?

Continue Reading >

Matlock Bobechko | First published on August 8, 2021 – 2:00 PM EST

[1] Christopher Hitchens, The Portable Atheist, Introduction, xiv.

[2] Richard Dawkins, River Out of Eden: A Darwinian View of Life (1995).

[3] PZ Myers, Morality Does Not Equal God. Science Blogs. Published on August, 2009.

https://scienceblogs.com/pharyngula/2009/08/morality_doesnt_equal_god.php

[4] Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values, 27, 29.

[5] J.P. Moreland, Scientism and Secularism: Learning to Respond to a Dangerous Ideology, 26.

[6] J.P. Moreland, Scientism and Secularism: Learning to Respond to a Dangerous Ideology, 45.

[7] Ronald Inglehart, Pippa Norris, Conflicts and Tensions: Why Didn’t Religion Disappear? Re-Examining the Secularization Thesis, 255-7.

[8] J.P. Moreland, Scientism and Secularism: Learning to Respond to a Dangerous Ideology, 50.

[9] Gowans, Chris, "Moral Relativism", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/moral-relativism/>.

[10] Alex O'Connor interviews Richard Dawkins. “Richard Dawkins | Outgrowing God | On Atheism, Ethics, and Theology (Podcast #10)” and “Richard Dawkins on Grounding Ethics Without God”. CosmicSkeptic YouTube channel. Published on September 19, 2019.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Sam Harris, The Moral Landscape: How Science Can Determine Human Values, 45.