Real Presence or Really Present?

Reflections on the metaphysical doctrines of Holy Communion concerning John 6.

“For the kingdom of God is not a matter of eating and drinking but of righteousness and peace and joy in the Holy Spirit.”

– Romans 14:17

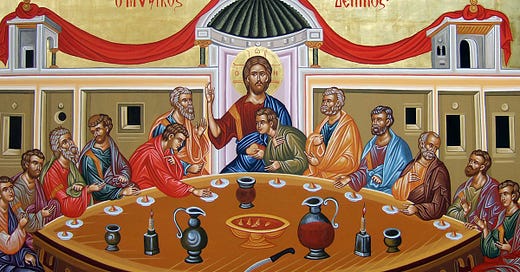

Dorothea Giannoukou, “The Icon of the Mystical Supper” — Antoniou.

Like so many things in Christian history, there is debate. A lot of debate. Communion is no different. Many a men have set their teeth on edge over this kerfuffle. Heck, even the term is contentious, whether it is called Holy Communion, Lord's Supper, or Eucharist (meaning, ‘thanksgiving’). There is a bloodsport over whether the elements served should be red wine or grape juice, there is a bake off over the use of leavened or unleavened bread, and there is a fermenting feud over its categorical role in salvation, whether it is a sacrament or ordinance, which is to say, whether Communion is a holy mystery or a mere memory, which I think sums up the main bout, among other peripheral scuffles. Point is, there is and will always be a few, at the very least, who eat sour grapes or go against the grain (pun intended). None so strong, however, as the prevailing metaphysical theories concerning John 6:

So Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you. Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day. For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink. Whoever feeds on my flesh and drinks my blood abides in me, and I in him. As the living Father sent me, and I live because of the Father, so whoever feeds on me, he also will live because of me. This is the bread that came down from heaven, not like the bread the fathers ate, and died. Whoever feeds on this bread will live forever.” (John 6:53-58)

Real Presence needs no introduction. It is a fully-baked and loaded term, garnished with denominational counterpoints and historical baggage. That is to say, it can mean a number of things. In Roman Catholicism, it is transubstantiation, which holds that the consecrated bread and wine transform into the flesh and blood of Jesus Christ, in substance but not in the accidents. It is what most people think of when they hear the term. In Lutheranism, it is sacramental union, which holds to four elements in holy mystery. In Anglicanism, it is either consubstantiation, which holds that the body and blood of Christ is present alongside the substance of the bread and wine, corporeal presence or pneumatic presence. In Reformed ecclesiology, it is simply spiritual presence, which more so attempts to remove any “carnal” or physical union with the bread and wine to avoid cannibalism (Westminster Confession, Chapter 29.7, 8). Orthodox, however, seem much more open to any metaphysical explanation—they do not have a formal definiton, but leave it to divine mystery.

As far as I can tell, no one can actually know if the bread and wine fully turns 1:1 into the physical flesh and blood of Jesus Christ. Not even Roman Catholic priests who consecrate the elements by retaining the exact words of institution (or the verba) spoken by Christ himself (Mark 14:22-26; Luke 22:14-23; 1 Corinthians 11:23-25), even though they predominately espouse a corporeal, substantial presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and that all of Christ is present in body, blood, soul, and divinity. It really seems to be a nominal affirmation or an appellation of a physical consumption. How so? Roman Catholicism teaches that the appearance (or to use Aristotelean vernacular, the “accidents”) of the elements do not physically change. There is no microscope, DNA test, radiocarbon dating method, or particle accelerator that can be used to scientifically prove that the organic material of bread and wine fully transform (1:1) into the true flesh and true blood of Jesus Christ, especially the same flesh/blood on Calvary two millennia ago. It cannot be achieved by the canons of observation, experimentation, testability, and repeatability—not by taste, touch, smell, sight, or ear. The elements only change at the ontological level, not on the level of appearances—whatever that looks like. Think of it like so: If the total sum of physical reality is like a painting on a canvas, where the stuff we see around us is the paint, such as people, cars, trees, houses, tables, bumblebees, microbes, bacteria, electrons, et cetera (this would be level of appearances or “accidents”), then the ontological level of physical reality is about the canvas and how the canvas binds the paint to itself. It is the most fundamental aspect of physical reality. In a sense, then, the bread and wine is the paint that masks Christ’s flesh and blood which is the canvas.

So, with that said, I am a bit perplexed; how is Communion truly the flesh and blood of Jesus if it is not fully the physical flesh and blood of Jesus? It does not seem truly physical because it is not fully flesh and blood at this point, even if transformation is necessary. In other words, when Christ says, “For my flesh is true food, and my blood is true drink” (John 6:55), what does He mean by “is” and what does He mean by “true”?

“True” Food? “Is” Flesh?

To add more fuel to the fire, here, even the sparse testimonies in Roman Catholic history where the priest claimed that the consecrated bread truly turned into actual flesh and the consecrated wine truly turned into actual blood—a miracle by all accounts—not a single one of them distributed the elements to be eaten or drunk. That would be cannibalism, and Roman Catholics are not cannibals (even though it may sound that way in word, it is not what they affirm in doctrine, practice, or belief). But if they were to eat the “true” flesh and drink the “true” blood of Jesus Christ, why not the appearances, too! Early Church father Irenaeus substantiates this Eucharistic understanding, that the elements are not physically the bread and wine, when fellow saints were forced to eat human flesh and drink human blood in mocking protest against the practice of Holy Communion:

“For when the Greeks, having arrested the slaves of Christian catechumens, then used force against them, in order to learn from them some secret thing [practised] among Christians, these slaves, having nothing to say that would meet the wishes of their tormentors, except that they had heard from their masters that the divine communion was the body and blood of Christ, and imagining that it was actually flesh and blood, gave their inquisitors answer to that effect. Then these latter, assuming such to be the case with regard to the practices of Christians, gave information regarding it to other Greeks, and sought to compel the martyrs Sanctus and Blandina to confess, under the influence of torture, [that the allegation was correct]. To these men Blandina replied very admirably in these words: “How should those persons endure such [accusations], who, for the sake of the practice [of piety], did not avail themselves even of the flesh that was permitted [them to eat]?” – Irenaeus (Fragment 13, emphasis added)

So I ask, again: What does Christ mean by “true”?

If you’re Catholic, I hope you can see the difficulty, here. Christ is not partially man, nor does God simply mask His appearance in the shape of a man—Christ is fully God and fully man, He is truly man and truly God. When something is true, it means in all respects, not in some respects—unless that truth is referring to something else, of course. Now one could counter-argue that the loss of a limb doesn’t make you less human, and the same could apply with Communion, and they would be right! But that is not quite what I’m getting at, here. There is no way to physically tell if the Eucharist is truly the body and blood of Christ. It is not a matter of losing something that was there, it was never there to begin with—it must be consecrated. So, if it is not possible to physically tell, then I think it is fair to affirm, or at least assume, that it ceases to be physical. For that reason, if the elements are not fully physical, the elements cannot be truly physical, which hurts the overall point Christ is making if you interpret John 6 in this way. Granted, no one has seen the depths of where the soul and body meet, either! So who am I to dogmatically say, “Absolutely, no”. All views on Real Presence affirm that Christ is, or is in, or is by the bread and wine but with different metaphysical explanations as to how this is conceivable. Yet, all the above theories sans Orthodox dogmatically reject the other, charging one another on accounts of cannibalism or impanation.

If I’m being honest, I’m slightly confused as to why.

For instance, some Anglicans believe in the consubstantiation, which is a spiritual consumption. Catholics believe in an ontological consumption, which is mystically a corporeal consumption. Frankly, as far as the laity is concerned, it sounds a bit like semantics. The metaphysics do not sound a whole lot different than the Anglican view, given that the elements do not fully become Christ’s physical body. Who is to say the canvas is not spiritual? The spiritual intertwines with the physical, one effects the other necessarily. There is overlap, friction, and tension between the two worlds once and yet unified. As Paul recites, “In Him [God] we live and move and have our being” (Acts 17:28). Similarly, like paint covering a canvas, the body houses the soul—you cannot see the soul, but the soul is bound to the flesh and effects it. There is a higher mystical union between soul and body that which was knitted together in the womb, as there is a mystical relationship with the heavenly counsel and creation. For is it not true that if someone consciously continues to sin in the flesh, that their behavioural patterns will change their character? (1 Corinthians 15:33) Sinning in the flesh pours out of spiritual desires and will have both physical and spiritual consequences, which also has eschatological implications on the soul and body come judgment Day (Matthew 10:28). The two are interwoven necessarily, though separate, and are momentarily disunited upon first death only to be reunited on that Day. And because of that, a real spiritual Presence seems to bind some aspect or relation of physicalness to it, though the spiritual seems to be of a higher necessity than the physical, for “It is the Spirit who gives life; the flesh profits nothing” (John 6:63).

Be that as it may, a metaphysical disagreement is also not warrant to reject transubstantiation wholesale. All doctrine requires a Scriptural basis and historical support. Some vehemently reject a change of substance because it has no biblical evidence, it is too Aristotelian, or it seems to necessitate cannibalism when consumed. If we save what a doctrine might suggest or logically entail for another day, it does seem that Justin Martyr, born thirty years after the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70, may have held to a similar process where a real substantial change from common to holy takes place by the power of the Word of God in prayer (1 Timothy 4:4-5)—take a look:

“And this food is called among us Εὐχαριστία [the Eucharist], of which no one is allowed to partake but the man who believes that the things which we teach are true, and who has been washed with the washing that is for the remission of sins, and unto regeneration, and who is so living as Christ has enjoined. For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as Jesus Christ our Saviour, having been made flesh by the Word of God, had both flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word, and from which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that Jesus who was made flesh.” – Justin Martyr (First Apology, chapter 66. Emphasis added)

To provide clarity on this, Justin does not believe he was committing cannibalism in keeping such practice according to the greater context of his Apology:

“And whether they perpetrate those fabulous and shameful deeds — the upsetting of the lamp, and promiscuous intercourse, and eating human flesh — we know not; but we do know that they are neither persecuted nor put to death by you, at least on account of their opinions. […] And when the president has given thanks, and all the people have expressed their assent, those who are called by us deacons give to each of those present to partake of the bread and wine mixed with water over which the thanksgiving was pronounced, and to those who are absent they carry away a portion.” (Ibid., ch. 25, 65)

As you can see, even Justin is affirming ‘He is, but isn’t’, or a ‘now, but not’ approach to Holy Communion. The elements are somehow the body and blood of Christ yet the bread and wine also, not human flesh but truly Christ’s flesh. He believes there is a sanctified “transmutation” that takes place in prayer. How does that work, exactly? I do not know. God knows. So to quickly pivot back—what does Christ mean by “is”?

Perhaps Christ gives us the best semantic range of His use of ‘is’ in spite of our limited understanding. We get a glimpse in John 1:19-23, when the Jews sent priests to ask John the Baptist, “Are you Elijah?” He responded, “I am not.” Instead he identifies himself with Isaiah 40:3, not with Malachi 3:1, 4:5. Yet, Jesus instructs His disciples differently, “For all the Prophets and the Law prophesied until John, and if you are willing to accept it, he is Elijah who is to come. He who has ears to hear, let him hear.” (Mathew 11:13-15, emphasis added) John the Baptist is both the fulfilment of Isaiah and Malachi. This is evidenced in Matthew 3 when he “wore a garment of camel's hair and a leather belt around his waist, and his food was locusts and wild honey” whilst “preaching in the wilderness”, which are characteristics that describe Elijah exactly. This is not reincarnation. John is not a vessel to embody the soul of Elijah. The point is, he is Elijah, yet he is not Elijah. He is the spirit and power of Elijah, but not the person and body of Elijah (Luke 1:13-17), which strongly suggests a distinction between soul and spirit, in my humble opinion. I think it is the same way with Communion: It is, but it isn’t.

What is the right view?

For these reasons, I don’t think it is wise, nor do I think we can, dogmatize one particular metaphysical view so long as the words of institution are retained, which is also why I think the Orthodox may have it right, here—mystery is emphasized, metaphysics isn’t dogmatized, and memory is a consequence of ritualization. Though, the Anglican notion of a sacred spectrum of Eucharistic views with bookends of doctrinal permissibility seems wise, given the evangelistic heart of Christ’s sacrifice and that it is possible for sacred objects, practices, and persons to have a temporal holiness (or a holiness by proximity) in Scripture and are not saved, so why not certain doctrines for the time being?—if held in honest tension? (1 Corinthians 10:27-33; Romans 14:13-23; cf. 2 Kings 18:4-6; 1 Corinthians 7:14-16). But I digress—for another day.

Well, that’s enough breadcrumbs for today. Though, admittedly, I’m in state of intellectual limbo regarding my metaphysical view on Communion and lean toward a spiritual real Presence with no particular ties to how it works, I really don’t think I need to. It is truly a profound mystery and, therefore, a matter of discussion, not of division. It would do us well to take Solomon’s wisdom to heart: “Trust in the Lord with all your heart, and do not lean on your own understanding.” (Proverbs 3:5) In the same way, we ought not to lean on our metaphysical understanding. Rather, we ought to lean on Christ, and He will keep our paths straight and narrow. A fact we should all be Eucharistic about come Thanksgiving.

More on Real Presence again next entry.

Matlock Bobechko | October 4, 2023 – 10:00 AM EST

“I don’t think it is wise, nor do I think we can, dogmatize one particular metaphysical view so long as the words of institution are retained, which is also why I think the Orthodox may have it right, here—mystery is emphasized, metaphysics isn’t dogmatized, and memory is a consequence of ritualization.”

This seems to be a bang on point, and generally where I’ve settled on the matter. Christ is really present, and the elements are not just stuff. I just have to trust Christ in that and recognize that it’s too big for me to grasp. This is healthy.

Really interesting connection about John the Baptist being Elijah in spirit, yet not being Elijah and how that might relate to communion.